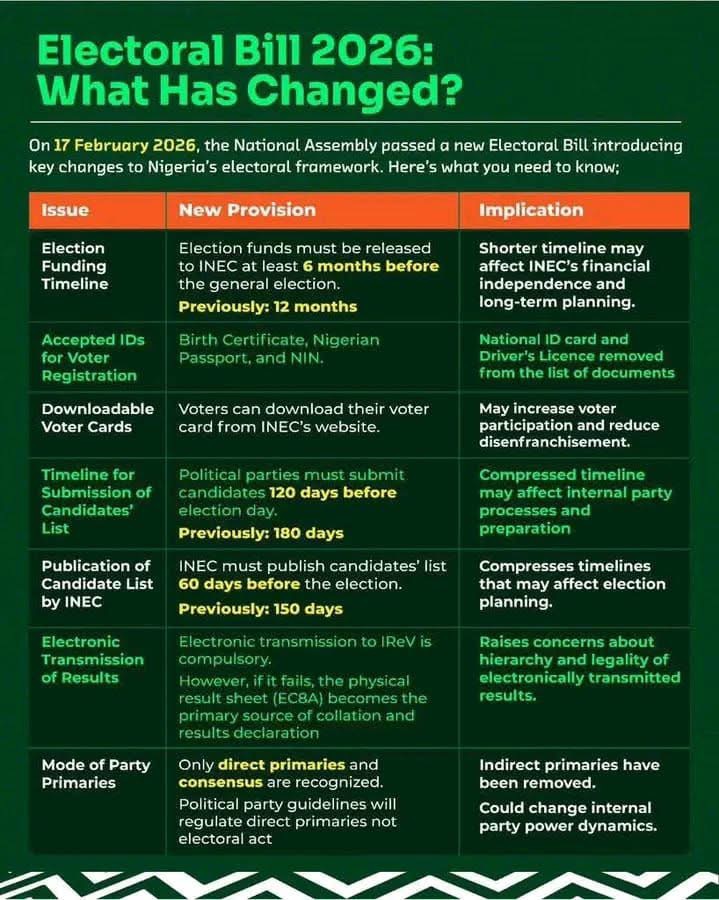

From the look of things, Nigeria’s National Assembly has tactically harmonised both chambers on the Electoral Amendment Bill 2026, thereby eliminating the necessity for a conference committee. With identical versions now passed by the Senate and the House of Representatives, the Bill may have to await the presidential assent.

At the core of the amendment are three major provisions relating to electronic transmission. First is the mandatory Electronic Transmission of Results. And second is the statutory Recognition of the IREV Portal. The third is the fallback to Form EC8A in Cases of Communication Failure.

Under the proposed framework, where there is no communication failure, results recorded at each polling unit on Form EC8A, duly signed by the Presiding Officer and countersigned by party agents, must be uploaded to the IREV portal immediately after announcement.

Where electronic transmission fails due to communication challenges, the duly completed and signed EC8A becomes the primary document for collation. What this means therefore is that where electronic transmission succeeds, the electronically transmitted result prevails in the event of discrepancies during collation. It is otherwise where reverse is the case.

Our legislators appear to justify this proviso as a pragmatic safeguard against any anticipated technological or network failures that may disrupt or invalidate the electoral process.

Stakeholders have, however, expressed concerns,

despite this legislative rationale. Critics argue that the fallback clause may inadvertently create a window for a possible manipulation. Arguably, given that we have achieved improvements in Nigeria’s telecommunications infrastructure, some consider the proviso unnecessary and potentially capable of generating confusion, evidentiary disputes, and post-election litigation. Although the Bill has passed both chambers, public confidence remains cautiously divided.

Recommendations from me for Institutional Clarity:

If this agreed version becomes law ahead of the 2027 General Elections, certain regulatory clarifications from INEC will be indispensable. They are that INEC Guidelines must mandate immediate electronic transmission upon completion, announcement and signing of results at the polling unit, in the presence of party agents, security personnel, and voters. The temporal element must be precise to prevent delayed uploads that may undermine transparency. Secondly, there must be clear definition of what constitutes “Communication Failure”.

The Guidelines must clearly define what constitutes “communication failure” and

who determines the existence of such failure at the polling unit. The objective threshold or duration before failure is declared must also be spelt out clearly.

We must note that where clear parameters are absent, discretionary interpretation may fuel avoidable disputes and election petitions. And finally political parties must invest in voter education and deploy competent, technologically literate agents at both polling and collation centres. The success of any electoral reform depends not merely on statutory text but on operational vigilance. All political parties must take note of this advice and strategize appropriately.

Amid the intense focus on electronic transmission, a less discussed but critical development appears to be the removal of the reform previously introduced under Section 137 of the 2022 Electoral Act, which aimed to reduce the burden of calling multiple polling unit witnesses where documentary evidence suffices.

Judicial precedents and interpretations have consistently required petitioners to call witnesses from each disputed polling unit, even where documentary irregularities are apparent on the face of the record. Reform on that section became necessary and it was agreed that witnesses are no longer necessary in the face of overwhelming reliable documentary evidence. That reform did not scale through by my observation. If the reform is indeed removed or diluted which nobody seems to notice, litigants will continue to face the onerous obligation of producing agents as witnesses from every contested polling unit in spite of limited time frame to prove his petition.

This unnoticed provision in the new amendment bill has profound implications for access to electoral justice and will require my deeper examination in subsequent analysis.

The immediate constitutional question now is whether the President will assent to the Bill, particularly in light of civil society advocacy urging him to withhold assent over the “transmission proviso”.

The coming days will clarify the executive’s position.

While the amendment may not represent the full spectrum of reforms many Nigerians desire, it nonetheless signifies institutional movement. Electoral reform is evolutionary and not necessarily revolutionary.

Nigeria remains our only country. We must not pray for its failure. Our collective vigilance, goodwill, and commitment to electoral integrity must guide the process forward.

Progress may be incremental, but with sustained institutional engagement and civic responsibility, the desired destination is attainable.

Let us have faith and keep hope alive!

*Dr. M.O. Ubani, SAN*

Legal Practitioner & Policy Analyst